Five PCT Hiking Tips for Success in the San Jacinto Mountains

Russ entering the San Jacinto Wilderness on his 2022 Pacific Crest Trail thru-hike

A place where your wildest dreams and greatest fears come true

For me, that is what the San Jacinto Wilderness represents.

In March 2020, I set foot on the Pacific Crest Trail from Campo, California having read up about the conditions in the San Jacinto Wilderness. At just 151 miles into my trip (less than two weeks in) I faced a high-alpine environment, freezing temperatures, altitude sickness, snow, ice, and strong winds. All of which I had experienced before at home in the UK and on my trips to the Himalayas and hiking up volcanoes in SE Asia.

I carried winter clothing and Kahtoola MICROspikes® from the start of my PCT hike and picked up an ice axe in Julian because I knew what conditions lay ahead.

Even with snow on day two, It surprised me how few people were carrying the equipment necessary to traverse the snow-capped mountains that lead the way for northbound hikers between the Paradise Valley Cafe at mile 151.8 to the Black Mountain Road at mile 190.7. Because of this, I decided to upload a video to my YouTube channel and write this article all about my experience in the San Jacinto Mountains, both in my 2020 traverse and my 2022 southbound thru-hike, hoping that it helps at least one hiker.

The hiking tips provided in this article are for informational purposes only and are not intended as safety advice.*

Watch my video where I go over the 5 tips in this article

The last time I saw Trevor (Microsoft) Laher

Before I dive into the 5 tips, I want to take a moment to acknowledge that I met Trevor briefly on my northbound attempt of the PCT back in 2020. We met in the desert and were leapfrogging (passing interchangeably along the trail), exchanging thoughts about our experience so far, until we made it to Montezuma Valley at around mile 100.

This is where I noticed that most of the hikers in our bubble weren’t equipped with the winter gear or skills necessary to traverse the San Jacinto mountain range. Another hiker and I decided to give the others (Trevor included) a brief overview of how to self-arrest with an ice-axe, and how and when to deploy traction devices in the hope that they would head into Idyllwild to equip themselves before heading up into the mountains, or decide to take an alternate, or skip the San Jacinto range altogether.

That was the last time I saw Trevor. He was sipping beer, laughing with friends and having the best time. It was an honor to meet such a bright and kind young man. I wished him and the others a good night before clambering into my tent for some rest.

The next morning I decided to wake up early and head off to traverse the San Jacinto mountains alone.

Why?

Because I knew that on my own I’d be able to make quick decisions should I need to change my plans. While traversing slopes I knew I’d be able to take my time without the influence of other hikers either in a hurry or taking too long so that the cold set in. This isn’t to say that hiking alone is always safer, it was a personal decision I made based on my experience level, and it paid off.

I traversed Apache Peak and the following slopes successfully, I pitched my tent at mile 175.4 just before a terrible storm hit, dumping snow with temperatures plummeting to around -15°C. This storm made the conditions on the section I had just traversed far worse.

The accident site at Apache Peak the day before Trevor’s accident in March 2020

The accident site on my soutbound traverse 2 years later in November 2022

I made it down to Idyllwild the following afternoon and a day later I discovered that Trevor had sadly perished at Apache Peak around mile 169.5.

I was saddened and shocked that someone I had just met was no longer with us to enjoy the trail. It made the next 25 miles almost unbearable and for that reason and many others, I decided to abandon my 2020 PCT thru-hike and return when Covid-19 had passed.

The Tips

Tip 1: Check the San Jacinto Trail Report

The San Jacinto State Park section on the Pacific Crest Trail harbors roughly 15% of the fatalities along the entire route every year; making it the most dangerous part of the PCT. That’s what Jon King the creator of the San Jacinto Trail Report told me upon my arrival to Idyllwild in March 2020.

The San Jacinto Trail Report is a valuable, free resource for anyone hiking the San Jacinto mountains, whether you’re a PCT thru-hiker or not. For me, I was able to see photos of the conditions that I’d face and which alternates I should take to avoid the most dangerous sections.

Jon regularly makes his way up to San Jacinto Peak along the Pacific Crest Trail, and its intersecting routes multiple times a week in all weather conditions to make the report possible.

You can read the latest reports on trail and weather conditions at sanjacjon.com.

Subscribe to the San Jacinto Trail Report on YouTube.

Please consider donating to the San Jacinto Trail Report on the donate page.

Tip 2: Bring the Right Equipment

The right equipment depends on the conditions and your planned route, but for thru-hikers in general it’s all about carrying less and hiking more, I get that. However, as the saying goes, it’s better to carry it and not need it, than to not carry it and need it.

This is why I started my Pacific Crest Trail thru-hike with winter clothing and traction devices from the Mexican border and I did not regret it. From day two I had snow and ice up at Mt. Laguna and the trend continued.

Sure, if you’re starting in mid-May or June, it’s unlikely this will be the case, but storms coming in carry severe bands of harsh weather in bursts before returning to warm, bright sunshine in Southern California.

For these reasons, I have chosen to feature these items as essentials at a minimum for traversing the San Jacinto mountains early in the PCT hiking season. Be sure to check the San Jacinto Trail Report for more detailed guidance on the equipment required for the conditions from Jon King; a trained professional.

Traction Devices

Excellent on flat, icy terrain. traction devices (Kahtoola MICROSpikes®) are light, easy to deploy and provide great traction on ice and compacted snow. In retrospect, stiff boots and crampons would have been more suited for my traverse, but I had my ice axe to cut steps where kicking steps with trail runners was more difficult.

MICROSpikes® (from Kahtoola) applied to my Altra Lone Peak 4.5 trail running shoe

MICROSpikes® inside their tough stuff sack

MICROSpikes® out in the field

Ice axe

Having an ice axe to self-arrest in the event of a slide could save your life. They also provide more stability on steep slopes than a trekking pole and can be used to cut steps into the slope for better footing.

A Grivel Helix ice axe

The head of the Grivel Helix ice axe

Garmin InReach Mini

Carrying a GPS Personal Locator Beacon (PLB) with an SOS button will not only help to keep you safe but also other hikers around you.

The front panel of the Garmin InReach Mini

Weighing in at just 113g, weight saving is a poor excuse for not carryig one

Thick gloves

Many thru-hikers like to carry thin, light-weight gloves but these ski gloves saved my fingertips. It would have been impossible for me to set up camp in a hurry with numb fingers.

The pair of ski gloves I found that another hiker had discarded

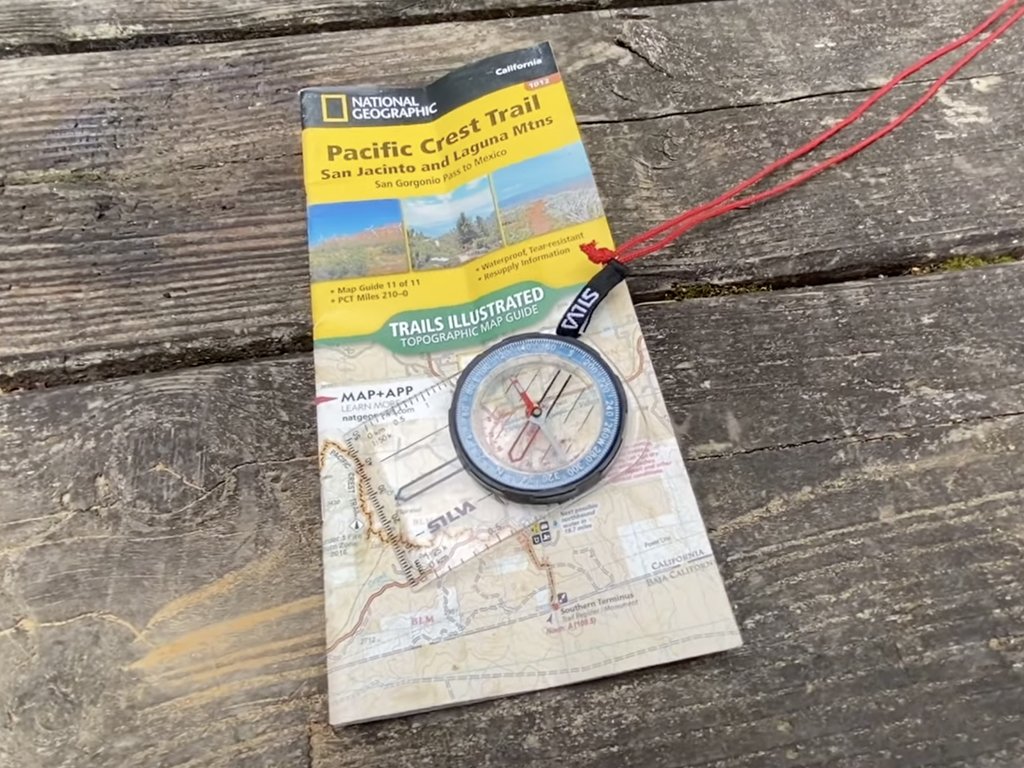

Map and compass

Farout is a useful tool; perfect for most of the Pacific Crest Trail. In high-alpine environments and winter conditions, you should never rely solely on battery-powered navigational tools.

If the trail gets covered in snow, or you get caught in a white-out and the battery on your phone dies due to the cold temperatures, a map and compass will still work.

Tip 3: Practice using the equipment

PRACTICE! PRACTICE! PRACTICE! It’s no good having the gear but having no idea how to use it. Always seek training from a professional on using the equipment in the field before you head into the field.

Tip 4: Plan ahead

Ensure you know how far you’ll be walking and which tent site you’ll stop at. Be clear on which alternates you’ll take should the conditions and terrain get too technical for your skill level.

Tip 5: Avoid Tahquitz Peak Trail and head to Idyllwild via the Devil’s Slide Trail

“It’s times like that I realize the thru-hiker mentality within me of not wanting to hike an extra mile and a half for the sake of getting to town 20 minutes faster could have cost me my life.”

On my way down to Idyllwild I thought I’d try the Tahquitz Peak Trail. It’s shorter than the Devil’s Slide Trail and presents itself 1.4 miles sooner at mile 178.0. As I began my descent the trail quickly disappeared under a thick blanket of fresh powder which covered a layer of hard ice. The camber of the slope increased dramatically within just a few paces and a sheer drop to my right awaited me should a slip turn into a slide.

I didn’t want to risk it, so I decided to turn back and head down Devil’s Slide at Saddle Junction just another mile and a half up the trail.

It’s times like that I realize the thru-hiker mentality within me of not wanting to hike an extra mile and a half for the sake of getting to town 20 minutes faster could have cost me my life.

I’m not a professional mountaineer and don’t claim to be, but knowing when to turn around and find a safer route is probably the most valuable skill I’ve learned.

Closing Thoughts

My wildest dreams came true on that lonely, icy traverse of the San Jacinto mountains. I had never seen such beauty mixed with a sense of pure respect for the hazardous conditions. Sadly my greatest fear also came true; losing a fellow hiker.

Trevor’s story has equipped me with a much deeper respect for snow and ice, as it has for countless other hikers. I leave you with a photograph of some flowers I left at the accident site as I hiked through the San Jacinto mountains southbound two years after his fatal fall in the hope that Trevor’s story and the information in this article equip you too with the same respect that it did for me.

The flowers I left at the accident site, November 2022

*Disclaimer:

The hiking tips provided in this article are for informational purposes only and are not intended as safety advice. While we strive to provide accurate and helpful information, hiking involves inherent risks, including but not limited to, rough terrain, unpredictable weather conditions, and encounters with wildlife.

Readers must understand that they assume all risks associated with outdoor activities and must exercise caution and judgment when hiking. It is essential to assess personal capabilities, prepare adequately, and follow established safety protocols before embarking on any outdoor adventure.

We strongly advise readers to obtain proper training, consult with experienced professionals, and familiarize themselves with local regulations and guidelines before undertaking any outdoor activities. The reader must take full responsibility for their safety, health, and well-being when venturing into the wilderness.

The authors and publishers of this article are not liable for any injuries, accidents, or damages that may occur as a result of following the suggestions or recommendations provided herein.